The 1918 Influenza Epidemic and the Bureaus of Immigration and Naturalization

In 1918, while World War I (WWI) raged overseas, Americans on the home front fought their own battle against an uncontrollable strain of influenza. The Spanish influenza epidemic spread quickly in the United States (U.S.) and abroad as it devastated civilian populations and military combatants. Soldiers transmitted the virus in their close living quarters and circulated it around the world as they travelled from base to base. Approximately 45,000 American service members died of influenza during WWI, nearly half of all American casualties. Eventually, the Spanish flu claimed over 650,000 lives in the U.S., just a fraction of its 20 to 50 million global victims.

The epidemic likely began in March 1918, when several cases of the virus were reported in Kansas and Georgia. After a brief hiatus, the deadly illness returned, spreading quickly as Americans struggled to detect its presence and institute effective defense measures. As the death toll in America continued to rise, panic spread across the country. The federal government worked to protect Americans and find a cure while also shielding its own employees from the disease. Under the Department of Labor, the Bureaus of Immigration and Naturalization (precursors to USCIS) implemented several health and safety measures. Despite cautionary actions, the Bureaus struggled to keep their employees safe during the influenza outbreak.

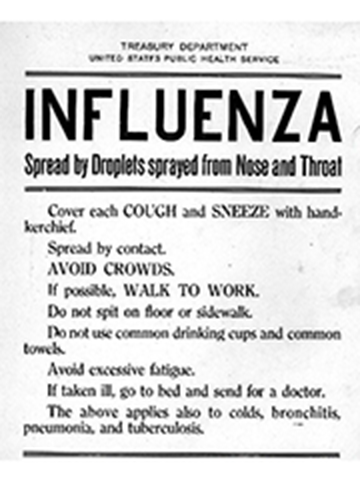

Unlike the standard strain of influenza, the 1918 outbreak of Spanish influenza disproportionately affected individuals between the ages of twenty and forty. While normally the healthiest part of the population, young Americans comprised approximately fifty percent of the victims. The unpredictability of the Spanish influenza created the impression among Americans that “the 1918… epidemic swept across the country like a hurricane, killing without discrimination.” Standard flu symptoms often quickly deteriorated into severe pneumonia. Sick individuals frequently bled from the mouth, nose, and eyes, lost oxygen, and consequently experienced skin discoloration. Victims could die within hours. Although government officials eventually determined that congested cities and crowded areas worsened the effects of the virus, many preventative measures assigned to the American public were ineffective.

Masks, such as these pictured on female clerks at Underwood & Underwood in New York, became part of the required workplace dress code following the 1918 Influenza. The Department of Labor hoped that covering employees’ mouths and noses would prevent the spread of infectious particles and successfully contain the disease. National Archives. . |

The Bureaus of Immigration and Naturalization needed to retain enough healthy employees to continue functioning during the wartime pandemic. After identifying the risks that large groups and air contamination posed to the spread of influenza, the Bureaus of Immigration and Naturalization implemented precautionary measures within the workplace. Face masks became required workplace gear, because officials believed that covering the face with gauze would prevent the transfer of illness. Departmental leadership prioritized fresh air and ventilation, and agency buildings were emptied twice a day in order to “flush out the spaces with new fresh air.” With these actions, the Bureaus attempted to protect their employees and to create safe workplaces.

The Bureaus of Immigration and Naturalization also cared for employees who fell ill with the influenza. In a 1918 letter to labor union leader, Samuel Gompers, former Bureau of Naturalization Chief Clerk, Paul Myer, relayed that “all employees reported ill are visited by volunteers of the Department and a report is made stating whether or not they are properly cared for.” The Department of Labor created a welfare committee “in order that the [agency] may keep in closer touch with its personnel, with the hope that it might be of assistance in time of sickness and need.” One report of a volunteer’s daily calls showed that on Oct. 18, 1918, the volunteer filled prescriptions for an ill employee, Miss Dove, and delivered food to sick individuals and families, including Miss Dove’s family.

The influenza pandemic also affected the immigration process, as immigration stations adapted to meet the needs of individuals who arrived sick with influenza. The Spanish flu hit the New Orleans Immigration Station when more than thirty detained immigrants developed symptoms. To accommodate the influx of sick patients, female quarters were converted into spaces for the isolation and treatment of victims. The actions and dedication of U.S. Public Health Service physicians paid off. Despite the surge in influenza cases at the New Orleans Immigration Station, no deaths had occurred as of December 1918.

While the 1918 influenza epidemic brought great fear and uncertainty to the U.S. and the world, the Bureaus of Immigration and Naturalization worked to prevent the spread of the flu and helped those in its sphere who became infected. Both Bureaus tried to establish the safest possible working conditions for their employees and minimize risk for arriving immigrants. Agency leaders coordinated to distribute protective masks, sanitize buildings, and improve air quality in indoor office spaces. The Bureaus’ treatment of healthy and sick government employees and the immigrants in their care demonstrated their dedication to their workforces’ well-being and their mission as the nation’s gatekeepers.

Women with the Red Cross conduct a demonstration at the Red Cross Emergency Ambulance Station in Washington D.C. during the influenza pandemic of 1918. Library of Congress. |