Profiles in World War I Immigration History: Fiorello La Guardia

Fiorello La Guardia during his first term in Congress in 1917, just before his World War I service. Library of Congress. |

Congressman and New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia (1882-1947) remains perhaps the Immigration Service’s most well-known former employee. As a young man, La Guardia worked as an interpreter at the Ellis Island Immigration Station. He eventually left the Immigration Service to pursue a career as a lawyer and a politician. The United States entered World War I (WWI) in 1917 while La Guardia was serving his first term in Congress. He volunteered to serve as a combat flyer, becoming the first sitting member of Congress to serve in the U.S. Army. As the children of immigrants, his wartime service represents the contributions that thousands of first and second generation Americans made to the American war effort.

La Guardia’s parents emigrated from present-day Italy shortly before he was born. La Guardia spent most of his childhood moving around the U.S. following his father’s assignments in the U.S. Army. They lived in South Dakota, Arizona, Missouri, and Alabama. In Mobile, Alabama, Fiorello’s father—a naturalized U.S. citizen—fell ill and received an honorable discharge from the army. The family returned to Italy in 1898.

La Guardia had hoped to attend an American university, but his family’s move to Italy required him to work instead. He obtained positions with the U.S. consular offices in Budapest, Trieste, and Fiume. While working in these consulates, La Guardia learned to speak German, Italian, Hungarian, and Croatian. These jobs also offered him an opportunity to observe the immigration process firsthand. Even during this early portion of his career, he showed an interest in reform and a desire to improve the immigration experience. For example, he insisted that emigrants receive medical inspections before boarding their ships to prevent them from being turned back upon their arrival at Ellis Island.

Major Fiorello La Guardia of the U.S. Army Air Service with Gianni Caproni, designer and producer of the Caproni line of airplanes. Photo taken in Milan, July 1918. La Guardia Collection, La Guardia and Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College, CUNY. |

After five years of working at the consulates, La Guardia returned to the U.S., where he took the civil service exam and accepted a position as an interpreter at Ellis Island. His mastery of several languages enabled him to easily communicate with many Southern and Eastern European immigrants. Adding to his linguistic skills, La Guardia learned Yiddish from the immigrants he encountered while working. At Ellis Island, La Guardia came to believe that language disparities resulted in unfair treatment of immigrants, especially those who faced exclusion hearings before a Board of Special Inquiry (BSI). La Guardia often argued with the BSI about charges he believed were unjustified. For example, he claimed that many immigrants excluded for mental illness were in reality only confused by the poor language skills of their interrogators. His assertions were outside of the scope of his duties as an interpreter and represented his early commitment to a lifelong advocacy on behalf of immigrants.

During his three years working at Ellis Island, La Guardia attended New York University’s law school in the evenings. After he received his degree, he applied his familiarity with immigration regulations to his work as an attorney. Immigrants often sought help finding jobs, obtaining housing, and otherwise settling into life in the U.S., and La Guardia took on many of their cases. He wanted to help immigrants resist the influence of political machines and receive fair treatment. Aware of the burdens faced by immigrants, La Guardia applied self-imposed regulations on the cases he accepted. To avoid charging unnecessary legal fees, he only accepted cases with a high likelihood of success and he refused cases that he believed his clients could solve on their own. In some cases, he even waived the fees entirely. By distinguishing himself from New York City attorneys who took advantage of newly arrived “greenhorns,” La Guardia established his reputation as a principled lawyer and a friend of immigrants.

La Guardia’s supporters among New York’s immigrant population helped elect him to Congress in 1916 as a Republican representative from New York. During his first term in the House of Representatives, La Guardia argued in favor of entering WWI. When the U.S. finally joined the war in April 1917, he successfully lobbied for a private bill that allowed him to become the first Congressman to concurrently have a commission in the U.S. Army.

In October 1917, La Guardia began his service as the second-in-command of an aviation training facility in Foggia, Italy, the town where his late father had been born. During his year of service in Italy, Fiorello supervised the training of American airmen and implemented solutions to many practical problems at his base. He improved food quality and quantity, addressed several public health issues, and ensured that his men would only fly structurally sound planes.

While in Italy, La Guardia also served on the Joint Army and Navy Aircraft Committee, gave propaganda speeches on behalf of the U.S., and assisted the Italian government in obtaining much-needed wartime resources. Near the end of his service, he obtained his wings and served as a combat flyer alongside Italian pilots. He worked as a pilot-bombardier and received the Italian Flying Cross medal for his services. La Guardia’s approach to leadership in the army matched his practices on Ellis Island and in his law career. He was pragmatic, energetic, and compassionate towards the well-being of those in his charge.

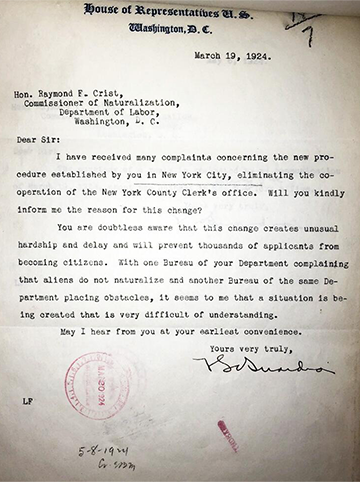

After the war, La Guardia resigned his seat in Congress, but returned to the House in 1922. Throughout his political career, La Guardia maintained his concern for immigrants. Even as a freshman Congressman, he advocated on behalf of immigrants even if his beliefs contradicted the official position of the Republican Party. In 1917, when Congress mandated literacy tests for new immigrants, La Guardia protested the use of the King James Bible because it could offend Catholic immigrants, who used a different version. He also strongly argued against the restrictive national quotas introduced in the Immigration Act of 1924.

As mayor of New York City during World War II (WWII), La Guardia insisted on empathetic guidelines for immigrant communities with ties to the wartime enemies. Some Italian immigrants, for example, attempted to send money to their family members in Italy. Although some people criticized this practice as assisting the enemy, La Guardia defended Italian-Americans’ desire to care for their friends and relatives. At the same time, he maintained fiercely anti-fascist ideals and he combated pro-Mussolini sentiments in the Italian-American population. His long-standing connections with Italian immigrant communities in New York and anti-fascist Italians in Italy made him a persuasive and popular voice on behalf of the war effort during WWII.

At the end of WWII, President Truman appointed La Guardia as director-general of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). This organization helped European refugees and worked to reconstruct the nations most affected by the war. While traveling in Europe, La Guardia relied on the same skills that made him a successful Ellis Island translator. He spoke directly to those affected by the war and he used his connections in the U.S. to implement solutions, such as exporting Midwestern grain stores to Europe. La Guardia also advocated for the U.S. to accept European refugees after the war. Although a lifelong politician, La Guardia grew disillusioned with the politicization of postwar relief. Frustrated by limitations on his humanitarian efforts, La Guardia resigned from the UNRRA after a year. He died a short time later, on Sept. 20, 1947.

Through his work as a civil servant with the State Department and the Immigration Service, a WWI soldier, a member of Congress, the Mayor of New York City, and the director-general of the UNRRA, Fiorello La Guardia served his country honorably in both peace and war. As a former Immigration Service employee, he remains an integral part of the history of the USCIS and its legacy agencies.